Andy Potts

It’s easy to assume there’s no romance in the bloated cash-cow that is the Champions League. Having carefully redrawn the rulebook so that Europe’s wealthiest clubs can qualify without the need to actually win anything, the house is stacked against the outsider, the little guy.

In recent years the competition has become a procession for Europe’s powerhouses, with teams from Eastern Europe serving as mere cannon fodder for the big four leagues to assert their TV-sponsored superiority.

So it was somewhat ironic that Rubin Kazan ended up taking their bow in a group which included four actual champions – as opposed to an assortment of affluent near-misses – yet still managed to land them with two of Europe’s biggest names plus local rivals Dynamo Kyiv.

But this outsider didn’t read the small print on their ticket for the UEFA gravy train, and rudely ignored the terms and conditions which apply to the quirky likes of BATE Borisov, Anorthosis Famagusta or, apparently, anyone from Scotland.

Nicking a draw with 10-man Inter was just about acceptable – even a cash cow needs a half-hearted attempt at a fairy-tale from time to time, and there’s nothing better than a plucky loser narrowly failing to progress from a group alongside the big boys.

But taking four points from Barcelona – including winning at the Nou Camp – just isn’t on.

It’s gone down a storm in Tatarstan, a region where sporting success has been carefully factored into the local government’s strategy over the past few years.

Dina Shakirova, a waitress in a bar just off Kazan’s main Ulitsa Baumana, described the scenes from the first game in Barcelona as “incredible”.

A packed house crammed around the TV screens erupted into an all-night party, with people “swinging from the lampshades, dancing on the tables, plates and dishes flying everywhere! The bar was almost destroyed!”

Her friend Elvira, a keen follower of Rubin, reckoned the whole campaign was “just a fairytale”.

“To beat Barcelona on their own pitch is just a miracle,” she said. “And then when we came back here we proved it was no fluke.

“These results will always be in my heart – now we’re hoping that we can continue the story.”

Even Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin got in on the act, according to reports from Tatar-Inform agency.

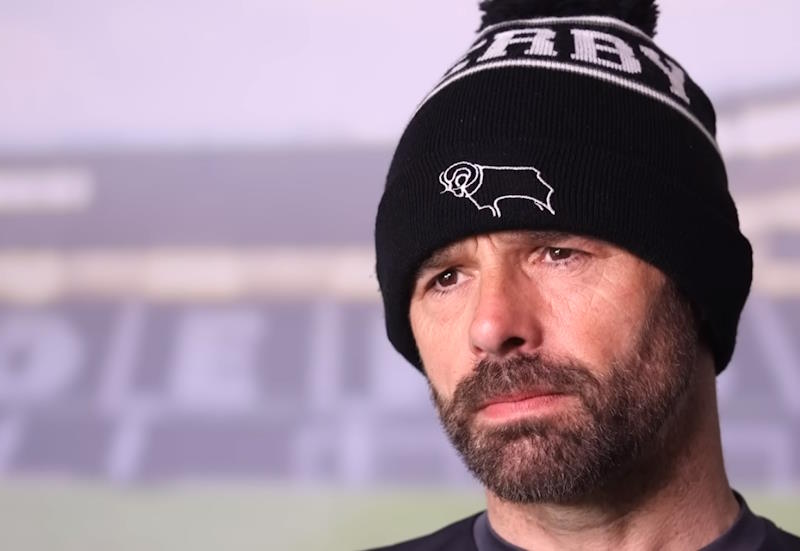

The normally quiet Rubin coach Kurban Berdyev admitted after the match that the former president – a Zenit St. Petersburg fan – was straight on the phone after the final whistle to congratulate him on “a good game”.

Putin often spontaneously greets Russian sporting success this way – after a 2006 Davis Cup triumph, tennis coach Shamil Tarpischev – another Tatar – was interrupted in a live TV interview to take a call from the then president.

For the Republic of Tatarstan, a mixed region of Muslims and Orthodox Christians which flirted with pursuing independence in the 1990s, sporting victories have become a rallying call.

Rubin’s march to the Russian Premier League title, in their 50th anniversary season, was the crowning moment of Tatar President Mintimer Shaimiev’s bid to bring glory to the region.

He turned out at the home game with Barca – braving -7 temperatures to cheer on the team and enjoy the appreciation of the local fans, who warmly approve of the local government’s efforts to help fund their teams.

Kazan, the regional capital, currently boasts Russia’s champions in football, volleyball and ice hockey, and is gearing up to host the 2013 Student Olympics and – hopefully – games in the 2018 or 2022 World Cup.

Rubin’s current home, the Tsentralny Stadion, has already been smartened up rather more than the average Soviet-era concrete bowl, and work on a new home is already underway across the river.

Meanwhile, the gleaming Tatneft Arena, sponsored by the local oil company, houses 8,000 raucous hockey fans when Ak Bars play in the Kontinental Hockey League and a modern sports hall just beyond the southern end of Ulitsa Baumana houses the city’s top-flight basketball team, UNIKS.

Related Articles: